Interview with Ali C

Night of the Fire, poetry, pain, healing

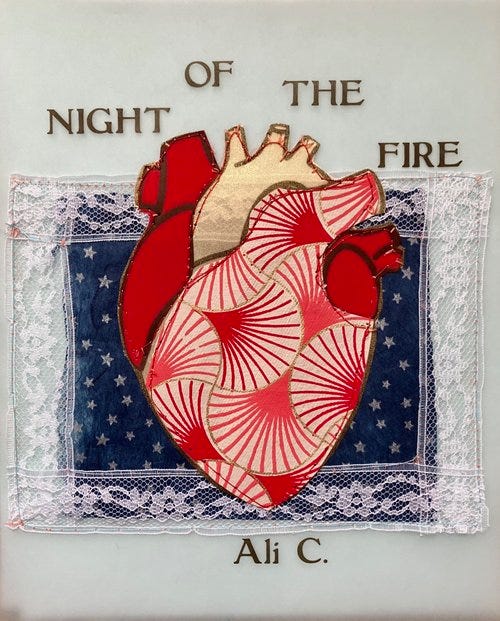

I was lucky to read an early copy of Ali C’s debut poetry chapbook Night of the Fire available from Ethel. I greatly admired the emotional power of these poems, the allusions to other writers and stories, and the brilliant details. I look forward to reading Ali C’s new poems for many years to come! And naturally, I had some questions.

Here’s Ali C’s quick bio:

Ali C is a poet and author of the chapbook, Night of the Fire, with Ethel Zine & Micro Press. He is an Emerging Creative Associate at New Writing North for 2025. You can learn more at www.alixyz.club

On with the interview!

I was taken by the powerful (and sometimes sardonic) rage expressed in poems throughout this collection, including "Penelope to Odysseus." Does writing this kind of poem feel cathartic? Or does it help you to concentrate feelings of rage?

My relationship with my art evolves as time passes, but PENELOPE TO ODYSSEUS was definitely one of the ones that felt cathartic when I wrote it. It wasn’t just about expressing anger—it was about distilling emotions I hadn’t allowed myself to be transparent about. Catharsis isn’t always about release, though. Sometimes it’s about precision—about taking emotions that feel chaotic and shaping them into something razor-sharp. In PENELOPE TO ODYSSEUS, rage isn’t just loud; it’s deliberate, sharpened, almost surgical. It’s an act of reclamation, a refusal to romanticise harm. The earlier version of that poem that got published in Aôthen Magazine still romanticised that suffering. There was a haunting erotic quality where I subconsciously infantilised myself, sort of made myself this Lolita-esque figure. I hate it. I only stripped that away in the few weeks before the chapbook was sent off to print.

But this poem isn’t just about personal betrayal—it’s about power. It’s about the nature of being with someone who saw the world in a way that fundamentally dehumanised people-of-colour, queer people, trans people, and people suffering through a broadcasted genocide. The poem makes fun of his “American moustache” and how he “grew into the blade they gave him” because there’s a kind of cruelty in how casually certain people wield their politics, how they treat their extreme right-wing ideology as a quirk rather than an active choice to align with harm. It’s easy to joke about bad politics when those politics don’t put your life at risk. There’s an unbearable loneliness in that, and you start to question what it means to be desired by someone who doesn’t see you as fully human.

So yes, PENELOPE TO ODYSSEUS was cathartic—but not in the way people assume. It wasn’t about feeling lighter. It was about carving out a space where my anger could exist without being silenced, about rejecting the idea that love can excuse harm. The politics of this poem are not incidental. They’re central. The rage in it isn’t just about a failed relationship—it’s about the ways power disguises itself as love. I keep returning to power dynamics more so in the poems I have wrote since completing Night of the Fire, not just my own but global ones as well.

Shadows keep appearing in these poems. How do you feel about shadows?

Mary Szybist, in an interview with The Paris Review, spoke about spending hours watching the Annunciation scene in a stained-glass window, trying to make sense of it. She reflected on the difficulty of seeing through the glass, saying, “Still, I could see shadows, light—hints of a world beyond the glass.” The poems in Night of the Fire exist in that same liminal space—where shadows suggest, distort, and sometimes briefly coalesce into moments of illumination, like in STAR-SPANGLED. Yet, there’s also a sense that the speaker is hallucinating colour, grasping at hope beyond this spectral world.

What fascinates me about shadows is that they aren’t just absence; they are tethered to us, an extension of the self—a ghostly double. Poetry is often described as a way of bringing obscured truths into focus, of making the unseen perceptible. In these poems, I think there’s an ongoing effort to define those dark shapes, to translate them into something understood. Night of the Fire ultimately dwells with shadows—even in the final piece, DEATH, there’s a line that compares suffering to a stalker whose “shadow burgeons each pocket of small light in the dark.” Shadows, in that sense, are inescapable.

That said, I hope my future work balances shadow and light more fully. There’s a reason a shadow is an extension of the self, but never the self entirely.

After describing the bombing of Palestine and other violent acts, you say, "Forgive me, the world ignores murder / because the blood is on the dead instead of our palms." Can you talk a bit about these (admittedly huge) issues, about how easy it can be to deny others' pain when our hands appear clean?

Yes, the Nova Massacre was horrifying. Violence in any form must never be minimised, though I would argue that an occupied people are allowed to fight against their oppressors and reclaim stolen land. Regardless, why does the systematic slaughter of Palestinians fail to warrant the same public outcry? Why must the colonial project that has persisted for nearly eight decades remain intact, unchallenged? And why must Palestinians constantly audition for the world’s empathy?

Hala Alyan wrote a powerful article on this for The New York Times in October 2023: Opinion | Even Before the Israel-Hamas War, Being Palestinian Was Controversial - The New York Times. That brutal reality is evident in how Palestinian suffering is dismissed, debated, or erased altogether. THE VENTRILOQUIST was initially a poem about my personal relationship with violence—how the city I was studying in felt overwhelming, suffocating. But violence is never just personal. Each week, I watched in devastation as mainstream media downplayed the relentless destruction of Palestinian lives. Moreover, the assault on Palestinian bodies extends beyond bombings and displacement. Sexual and gender-based violence, increasingly documented by the UN Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, is being weaponised as a tool of war to dehumanise and destabilise communities. Anne Krauthamer wrote a brilliant think-piece on how the West uses sexual violence to advance its interests that I strongly urge people to read: https://thebaffler.com/latest/grist-of-empire-krauthamer. Overall, the lack of empathy is staggering, and people who choose to ignore this suffering should be embarrassed.

At the time of writing this, in March 2025, DHS and ICE agents in the U.S. have illegally abducted Mahmoud Khalil, a legal US resident, and placed him in indefinite detention. His wife—eight months pregnant—is a US citizen. Resistance to fascism and state violence is now met with the erasure of First Amendment rights. The Trump administration weaponises antisemitism to silence any opposition. Universities, instead of defending academic freedom and human rights, has been complicit in this violence, failing Khalil and countless others. Denial and ignorance are no longer options. The illegal detention of Khalil is one instance in an ever-expanding web of repression. This is how oppression works—it creeps from the periphery to the centre, from the most marginalised to the supposedly protected. If we do not resist, at every level, we allow it to continue.

Most importantly, I urgently ask people donate to fundraisers and charities, whether it be UNRWA, Doctors Without Borders, or individual funding campaigns over at gaza funds dot org. Friend and poet, Maria Gray, is a co-host of the Alghorah family fundraiser, which you can find access to here: Fundraiser by Eli N : Help the Alghorah Family Evacuate Gaza. But there are many others as well, so there shouldn’t be an excuse not to offer even a small helpful gesture.

Could you include a section of one of these poems that you especially love and talk a bit about what it means to you?

My poem GENTLEST OF BLEEDING THINGS is special to me. I wrote it in October 2024 with the intention of placing it in a future project, but I felt it belonged in Night of the Fire—not only to offer contrast but to extend a hand to those who might need it. So much of the chapbook lingers in pain, but this poem is a reminder that healing, solitude, and self-discovery are not only possible but necessary.

I remember visiting Tynemouth, standing at the edge of the sea, and feeling captivated by its quiet vastness. There was something profoundly soothing about the way the waves hummed, about how the water seemed to both hold and dissolve the weight of the world. Throughout the collection, the sea is often an image of violence and turbulence, a force that consumes—but here, it transforms. It becomes a space of clarity. It felt important to end the book with that shift, to let a moment of peace break through the darkness.

Somebody told me grief is the door

and not the room. I had spent most of my life

thinking each entrance, each slight

interstice in the walls was an invitation for darkness.

How I let it fester and saturate. How I allowed it

to tire me without letting me collapse

from it. When I wrote poems about trauma,

the words on the page shut their eyes,

and could not look at me again. I have tired language and

now I create sentences like journeys without destinations.

Today, I thought about Palestine,

the olives, the cafés peppering the shoreline,

the beautiful children, the pained sky waiting for silence

to speak again. I went down to the beach in the

afternoon for the first time in eight months.

On the sapphire of water, a boat circled

the palm of the ocean. On the boat,

bodies touched each other through the curtains of dream.

I have wanted to be a beautiful thing for all my life,

I’ve swarmed the world looking for it

without realising my face has been turned

away the whole journey.

Do you ever show your poems to the people who inspired them?

No. The only person I ever send my poems to—usually once they’re published—is my friend Ari. She’s been a big cheerleader of my work since the beginning, back when I vanished from the Internet and social media because I was too sad and spending my summer writing these poems, wallowing in self-pity. She’s truly the most intelligent and empathetic reader, and also just incredibly grounding. She gives advice like a sage but never pushes, and she always seems to know what I actually need to hear and learn.

She’s also a very talented visual artist. I had a series of poems I was working on in early spring centred around Pyramus and Thisbe, and she created this stunning piece of art in response to one of them. I really hope I get to share it one day—it felt like a true collaboration, not just in tone but in spirit. The colour palette matched the vibrancy and sensory textures of the world I was crafting.

As for the people the poems are about—specifically the men—I don’t think they deserve that kind of attention. Or access. Writing about those experiences is one thing, but giving them the chance to read or respond to it? That feels like a violation of everything I had to go through to reclaim my voice. A lot of them moved through my life with entitlement—entitlement to my time, my silence, my softness. There’s no way I’m handing them my work, too. Poems aren’t just art. They’re record, they’re memory, they’re sometimes the only form of truth-telling we’re allowed. To offer that to someone who harmed me would feel like giving them the last word, and I won’t do that. Maybe that sounds harsh, but I think you learn that healing sometimes means keeping the door closed. Writing is my way of letting things out—but not necessarily letting people back in.

What was the writing process like? How difficult is it to shift from writing a poem to assembling a collection of poems? Was it difficult to determine the order?

The process for Night of the Fire was a little strange. I didn’t plan to write a chapbook. Or publish it. I was mostly just trying to understand what had happened—these traumatic experiences that took place over the span of a year, and how I felt about them afterward.

At first, I was writing micro-fictions. Then a nonfiction essay. The poetry came out of that slowly. It wasn’t planned—it just felt like the only form that could hold what I was trying to say. The first draft leaned heavily on the micro-fictions. The second version tried to bring in tarot and fairy tale elements, but that didn’t feel right, so I let it go. The third draft was a kind of freefall—very experimental. Eventually, it took shape. What I’ve learned is: you can’t force it. Trying to push a project into a specific form before it’s ready just doesn’t work. You have to be okay with following the work, not leading it.

During that time, I was also figuring out what my voice even sounded like. And a lot of the time, I felt like I was just echoing the poets I was reading over and over again. A well-known writer once told me, “If you don’t feel another poet’s voice breathing down your neck, you’re not writing properly.” I thought that was helpful at the time, but looking back—it wasn’t. Anne Whitehouse once said in an interview, “If one is aware of the influence, then it’s not really an influence. It might be a model.” That stuck with me. Because during that phase, I was very aware of who I was reading. I was also thinking too much about what journals might want. And when you’re in that headspace, it’s harder to take risks. But those poets still taught me a lot. Especially that you don’t need to be explicit to write about violence. Sometimes what’s not said is more powerful than what is.

People sometimes ask if I’d change anything about the chapbook. The truth is—it’s such a conceptual book that I designed it to work like one long piece. Even without titles, I wanted it to feel like a kind of cycle. Almost like an epic poem about death: death as violence in EMBALM and death for the purposes of rebirth in DEATH. I wouldn’t replicate that for my full-length collection—it’s very specific, very experimental. But I’m glad I tried it. This one was an homage to my two favourite conceptual projects—Melanie Martinez’s Cry Baby trilogy and Ethel Cain’s Preacher’s Daughter.

If anything, I wish I had gone deeper into the politics of the ‘Odysseus’ relationship. It was racially charged in ways I didn’t fully address. At the time, I wasn’t ready to. That’s something I’ve only started processing this year. There’s irony in the collection that I think some readers might catch. Like using a Lana Del Rey lyric at the start of THE VENTRILOQUIST—it just felt right in the moment. But looking back, there’s something jarring about putting a line from such a hyper-American figure in a poem about Palestinian genocide—especially with the way that violence is funded. That tension was unintentional, but it says something.

Since finishing the book, my writing feels different. More certain and confident. I think not being constantly submerged in sadness has helped. There’s more distance now, which means I can see the work more clearly. I can tell what belongs in a poem and what doesn’t. That’s been a gift. It’s exhausting to live inside personally violent narratives for too long. At some point, you have to step back. You risk getting stuck—in your writing and in your life. Taking breaks is necessary. Letting yourself grow, heal, look in new directions. Healing doesn’t have to be antithetical to creation.

Who are some of your favorite poets?

It changes depending on what I’m writing, but while I was working on Night of the Fire, there were a few I kept coming back to—Carol Ann Duffy’s The World’s Wife, Leila Chatti’s Deluge, Gabrielle Bates’s Judas Goat, Maria Gray’s Universal Red. I was also reading Sylvia Plath and Mahmoud Darwish, kind of side by side. At the time, I needed work that didn’t flinch. That was important to me.

Sexual violence isn’t something you see covered deeply across whole collections very often, and I was trying to figure out how to approach it without losing the rest of the work to that one theme. Those poets helped me figure that out. Maria’s poetry especially made a difference in terms of understanding my own writing career. She’s close to my age, and seeing her write through difficult material gave me more confidence in what I was doing. It’s easy to feel like your work is too heavy or too different when no one around you is writing about the same things.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this idea Lana Del Rey mentioned in an interview—a term her psychic gave her, actually—called overculture. The idea that “most philosophers have described the timing of people’s creativity is that there is a general siphon that we can all draw from that collective.” That made sense to me. A lot of the poets I love feel like they’re in quiet conversation with each other. I see that especially with poets who write about religion and the female body. Most of them are women—Mary Szybist, Sarah Ghazal Ali, Leila Chatti, Gabrielle Bates, Marie Howe.

Since finishing the chapbook, I’ve been trying to read more widely—things that aren’t rooted in continuous personal violence or trauma. I’ve been enjoying Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, Camille Ralphs, Mary Ruefle, Maria Zoccola, Sara Lefsyk, Louise Glück, Katie Schaag, Natalie Shapero, and Fady Joudah. Nicole Sealey’s erasure of The Ferguson Report also deserves a special mention. Right now, I’m focused on building a stronger relationship with language and form. I’m taking my time with it.

What question would you like to be asked?

On a more sincere note, I’d like to be asked about joy. People often assume my writing exists solely in grief and rage, but there’s so much joy in the act of creation itself, in the friendships that have formed because of poetry, in the ways words can make sense of the world. I think it’s important to talk about the things that keep us here just as much as the things that wound us.

What an insightful read ❤️ Thank you for the kind words :)

Always cheering you on!!!

Ari x