Interview with Philip Graham

Free Little Libraries, Childhood, What the Dead Can Say, etc.

If you haven’t read Philip Graham before, take a peek at his Wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Graham_(writer)! There’s too much to be said about his life and work to fit here, but this gives us the highlights…Brooklyn-born, mentored by Grace Paley and Donald Barthelme, co-founder of Ninth Letter, Professor Emeritus at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, published in The New Yorker and all the rest. And he continues to write incredible stories and essays to share with us!

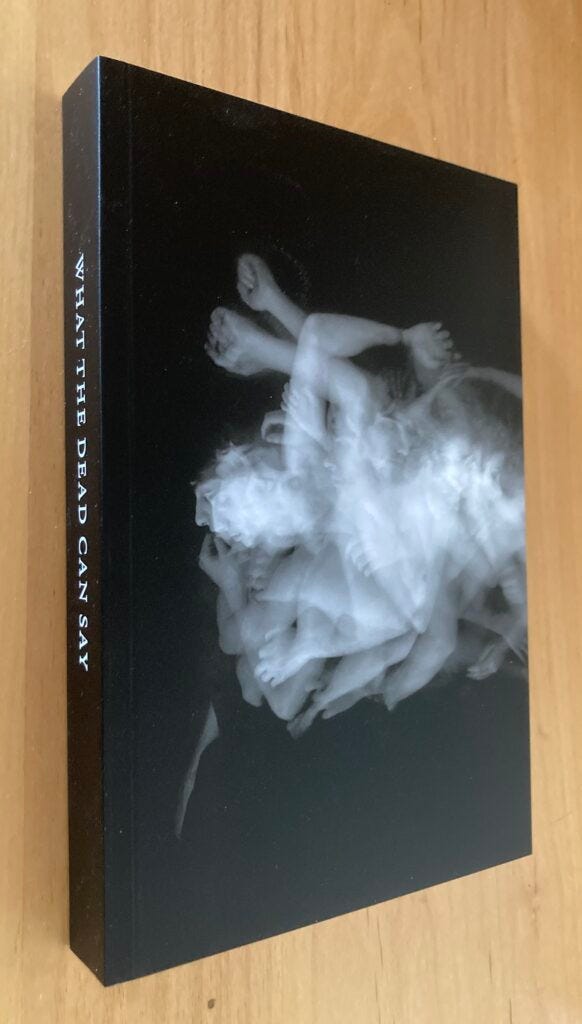

Recently, he completed a publishing experiment I found fascinating, where he printed limited copies of his book What the Dead Can Say (as “Author Unseen”) and made them available solely in Little Free Libraries across the US, and then launched yet another experimental project of publishing the book chapter-by-chapter online. To read about how he managed this cool project, check out this great interview with Michele Morano!

My interview is a bit abstract and meandering, as is my way. Here we go!

Ivy Grimes: What is some of the best advice given to you by your writing mentors?

Philip Graham: First, thank you, Ivy, for the occasion of this conversation—and this first question, which encourages me to warm up the Way-Back Machine.

In the mid-seventies, when I was studying with Donald Barthelme, I wrote very short stories. Donald, who was always trying to lead his students toward new possibilities, suggested that I should try writing a novel. At first this seemed like insane advice to me—I was still struggling to write past page three with my stories. All I could think of in reply was “I wouldn’t know where to begin.” Which was absolutely true! His response has since proved invaluable throughout my entire career: “Whenever I begin a novel,” he said, “the beginning never stays at the beginning. It ends up in the middle, or near the end. It never stays put where I started.”

This was an absolute revelation. Because I read books sequentially from first page to last, I’d unconsciously assumed that was how books got written, too. Instead, their various parts shift and negotiate, bubble up or vanish, until a sequence develops that, ideally, appears to have always been that way.

I would be remiss not to mention though, what I learned about writing from a class that wasn’t a writing workshop. As an undergraduate, I took modern dance classes, as research for a story that was then far beyond my budding skills as a writer. But steeping myself in the techniques of contemporary dance influenced my writing in ways I couldn’t have predicted. First, the physicality of those dance workshops, almost by osmosis, liberated the rhythms of my prose, un-stiffened the formality of my earliest attempts at writing. And whenever I participated in a dance piece being developed by a young choreographer, I became accustomed to moving as a character within a narrative that navigated three-dimensional space. This experience helped me to better imagine the scenes I was trying to create for my short stories. Now this doesn’t mean that I think all young writers should take contemporary dance classes. But certainly consider delving into photography, music, painting or whatever. You may find that some of the revelations offered by another art form can translate into your evolving words.

Ivy: In What the Dead Can Say and in your short stories, you explore the confusing world of childhood in a compelling way. What was your own childhood like?

Philip: Oh, this is a great question, and so difficult to answer. I grew up in an unhappy, dysfunctional family that pretended it was normal. Like living in fog but only being allowed to say the sky is blue.

The anthropologist Jules Henry (in his book Pathways to Madness) has observed that, from infancy on, children “imbibe” the universe through the often unspoken perspective of their parents. I think the great task of all children as they grow up is, first, to recognize this hidden structure inside them, and then find ways to use that structure, that perspective—whatever it may be—into something more constructive. A liberating insight for me was to think of my parents not as Mom and Dad, but as Edie and Bill—people with first names who’d had lives before becoming parents, who’d developed mysterious inner lives, and had mysterious lives outside the family setting.

And yet still you’re stuck with what you imbibed so long ago. What to do? Imagine your family has given you a terrible sweater—awful colors, wrong size, three arms not two, and so forth. It just can’t be worn. So instead, take it apart, thread by thread, and remake it into a cape, a comforter, a scarf, whatever. Turn it into something you can use.

For me, this re-imagining and remaking is how all artists, of whatever persuasion, can recast any serial sadness from their childhoods into serious adult work.

(Ivy’s note: I highly recommend Philip’s excellent essay on the subject of childhood trauma and writing, Something You Can Use: The Writer’s Self-Healing Wound)

Ivy: I love the idea of recasting the past. I wonder if these experiences gave you a more vivid sense of childhood, to portray it with such color and deep feeling.

Philip: Remembering is a complicated business. I believe that memories have shadows, and these shadows hide or protect a memory’s hidden significance. Why do we sometimes remember a seemingly random moment or event? The answer, I think, lies in the nurturing darkness of that memory’s shadow.

For instance, though my parents constantly argued, I can only remember the actual words of a single argument, and even then I can only remember a short snippet of their angry exchange, only about twenty words in all. And yet those few words affected my life in profound ways that initially I couldn’t fully fathom.

Over the breakfast table my parents had declared they’d never loved each other, though it was clear to me—at age eight—that one wasn’t telling the truth and the other probably was, and from those few words and the way they were spoken I learned—though without consciously knowing it—about the power dynamics of love, and the cost of loving too much and loving too little. Only fifty years later, when I had occasion to examine that neglected and nearly forgotten memory more closely, did I realize the significance of those few words on my life, which had led me to the woman I am still happily married to today. That memory was patiently waiting for a time when I’d be able to grasp not only its significance but why I’d stored it away in the first place. I think most vivid childhood memories are little potential novels, their shadows waiting to be decoded.

I would say that one of your great subjects as a writer is the in-between period of adolescence and young adulthood, that time when child-like wonder can be a powerful tool to interpret and navigate dangerous grown-up worlds. Your characters are often earnest, plucky voyagers possessed of a touching willingness to adjust to whatever strange rules or logic they encounter. I wonder what begins for you, a character or the world she finds herself in? Or do the two develop together?

Ivy: I often write about someone leaving one world for another. I wrote one story about a young woman kidnapped from the city and taken to the country, where she comes to understand the world of a strange family. More recently, I wrote a novel about two sisters who grew up alone with their mother in the woods until they are forced to leave and make sense of the community in the nearest town.

In terms of pluckiness and adjustment, I love the harrowing but optimistic novels of Barbara Comyns. Her heroines remind me of some of the late women in my family who encountered many trials (sickness, death, deprivation) and still maintained a funny optimism. When someone’s dying (even when it’s you), you might still enjoy painting your cabinets canary yellow. When you’re short on cash, you can still sing along with the radio, even if you can’t carry a tune. I often feel like I don’t belong in groups, like I don’t speak the same language as most other people, but the thread connecting me to others comes from that sense of joy and curiosity about the world. I don’t think that kind of optimism is infinite; I’ve seen its limits. I’ve told myself it probably won’t carry me along forever. I try to enjoy it while I can, though.

All that to say, I enjoy exploring the worlds of my stories, and my protagonists are often as confused as I am. Even when they’re elderly, they often have the attitude of adolescence, of leaving behind an intricate inner world to encounter a strange but lively outer world. Trying to understand. I think my characters emerge alongside the worlds of my stories, and I learn who they are as they encounter something external (something that at least appears to be Other).

I’m really interested in exploring psychology as I explore fiction. An unpopular pastime I have is psychoanalyzing the artist after I experience the art. I do this to myself and my work as well. Of course, I don’t include it in my reviews of others’ work…it’s a private practice! I love reading about Jungian analysis of stories and dreams, too.

I suppose that’s why I started by asking you about your childhood. One thing I find fascinating about interviewing you is that you’ve written so much and answered so many questions over the course of your impressive career, I wonder what is left unsaid. Can you think of something you’d ask yourself if you could, something no one’s gotten at yet that you want (or don’t want!) to express?

Philip: Ivy, you come up with the best questions.

I think I have not been asked how being a parent has influenced my life as a writer. Strangely enough, parenthood made me more prolific, not less. Even though I had less time to write, I found I made far better use of that time. No more hemming and hawing (or at least, not too much!) before settling into the daily thicket of writing. I have always been an active father (something my own father, for historical and personal reasons, had never been), and I never wanted to resent either of my children because I wasn’t getting any writing done. I became more efficient out of necessity, for the love of my kids.

Our two children also inspired me. Despite the constant setbacks of gravity and muscle control they learned how to walk! They learned English with a kind of joyful determination and then increasingly expressed their thoughts and defined their emotions. They were a master class on how to receive the world with wonder, and I did my best to learn from them.

Ivy: Since we’re on the subject of time and age, how does it feel to be able to look back on decades of your life as a working artist? Do you have the same artistic concerns you had years ago, or have certain shifts surprised you?

Philip: Though I’ve always written prose, my first published work—beginning in the mid-1970s—was influenced by poets like W.S. Merwin, Mark Strand, Adrienne Rich, Charles Simic, and others. I wrote prose pieces in a surrealistic style that lived in some uncanny valley between prose poem and short fiction. Eventually, the length of the pieces grew until I simply had to call them short stories.

But the main shift in my writing occurred when I lived in small rural villages off and on from 1979 to 1993 among the Beng people of Côte d’Ivoire, accompanying my wife, the cultural anthropologist Alma Gottlieb. That immersion taught me how much of culture is invisible, how much of it lives in people’s heads. And because Beng culture is so different—filled with spirits and the continuing influence of the ancestors, the social glue of ritual and the fear of witchcraft (to name just a few examples)—my earlier attraction to surrealism shifted. I became far more interested in the imagined worlds within people, and how our inner thoughts and beliefs influence and create the exterior world around us. So: a very specific blend of outer realism and the inner fantastic became the landscape I wanted to continue to examine as a writer.

And the culmination of that influence has been my latest novel, What the Dead Can Say, whose fictional landscape is the afterlife. The main characters are all ghosts, and the novel’s afterlife is similar to that of the Beng, where the dead exist invisibly among the living with their own vibrant social worlds.

As you’ve just mentioned about your own work—we writers like to explore different worlds!

Ivy: Very true! Speaking of which, where would you direct readers who are new to your world? Where should they begin (links appreciated!)?

Philip: Thank you for that offer, Ivy, I’ll try to keep it short!

If readers are interested in my latest novel, What the Dead Can Say (30 years in the making), they can follow this link:

https://www.whatthedeadcansay.com

While copies of the print edition of the novel were entirely deposited in Little Free Libraries across the country over a year ago and so are not easily found (though a fan recently sent me a photo of a copy she discovered in a little library inside the Owl Music Parlor in Brooklyn), this expanded digital version has extra scenes, audio clips, and evocative illustrations throughout.

I’m glad you gave a shout-out to the wonderful writer Michele Morano, and her interview with me about What the Dead Can Say. There’s also a recent essay I wrote that might be of interest—about the novel, its slightly mad distribution project, and the cultural diversity of our country—for the Persuasion Substack: “The Joy of Forgotten Books.”

My next book will likely be That’s the Way Fire Is, a collection of craft essays, on the art of fiction and nonfiction, that I’ve been writing/presenting over the past 20 years. You can find a small sampling from those more than 80 essays here:

https://philipgraham.net/selected-craft-posts/

Another possibility for my next book is an expansion of a series of music essays I wrote for 3 Quarks Daily. If you’re interested in the bizarro appearance but beautiful sound of a stringed instrument called a nyckelharpa; or the long journey to appreciate accordion music; why the pedal steel guitar is popular in Nigeria; or the glory of the musics of the former Portuguese empire, then look no further than here (audio clips abound!):

https://3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/author/philipgraham

Finally, if anyone is interested in my earlier fiction, it’s available now in Dzanc Books’ e-editions, including these two short story collections:

The Art of the Knock (https://www.dzancbooks.org/all-titles/p/the-art-of-the-knock-by-philip-graham) and Interior Design (https://www.dzancbooks.org/all-titles/p/interior-design-by-philip-graham)

Thank you, Ivy for this conversation. I am a huge fan of your work, and I have The Ghosts of Blaubart Mansion on pre-order. Can’t wait!

Many, many thanks, Philip!!

That’s an awesome interview! Love the advice about beginnings and the thoughts on memory

Yowza! The Boss of Questions meets the Boss of Answers! I love love love this interview.